- Home

- Mary Wisniewski

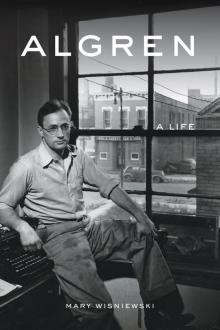

Algren

Algren Read online

A TIRELESS CHAMPION OF THE downtrodden, Nelson Algren, one of the most celebrated writers of the 20th century, lived an outsider’s life himself. He spent a month in prison as a young man for the theft of a typewriter; his involvement in Marxist groups earned him a lengthy FBI dossier; and he spent much of his life palling around with the sorts of drug addicts, prostitutes, and poor laborers who inspired and populated his novels and short stories.

Most today know Algren as the radical, womanizing writer of The Man with the Golden Arm, which won the first National Book Award, in 1950, but award-winning reporter Mary Wisniewski offers a deeper portrait. Starting with his childhood in the City of Big Shoulders, Algren sheds new light on the writer’s most momentous periods, from his on-again-off-again work for the WPA to his stint as an uninspired soldier in World War II to his long-distance affair with his most famous lover, Simone de Beauvoir, to the sense of community and acceptance Algren found in the artist colony of Sag Harbor before his death in 1981.

Wisniewski interviewed dozens of Algren’s closest friends and inner circle, including photographer Art Shay and author and historian Studs Terkel, and tracked down much of his unpublished writing and correspondence. She unearths new details about the writer’s life, work, personality, and habits and reveals a funny, sensitive, and romantic but sometimes exasperating, insecure, and self-destructive artist.

Copyright © 2017 by Mary Wisniewski

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-532-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wisniewski, Mary, author.

Title: Algren : a life / Mary Wisniewski.

Description: Chicago, Illinois : Chicago Review Press Incorporated, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002793| ISBN 9781613735329 (cloth : alk. paper) |

ISBN

9781613735350 (epub) | ISBN 9781613735343 (kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Algren, Nelson, 1909-1981. | Novelists, American—20th century—Biography. | Authors, American—20th century—Biography.

Classification: LCC PS3501.L4625 Z95 2017 | DDC 813/.52—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002793

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To Mitch and Bonny, Lucian and Gabriella, and Frank and Sophie, the kings and queens of old Polonia.

CONTENTS

1 Childhood Days

2 College and the Crash

3 Prison and Somebody in Boots

4 Marriage and the WPA

5 Polonia and Never Come Morning

6 Polonia’s Revenge, and Algren in the Army

7 Beloved Local Youth

8 Golden Years

9 The Walls Begin to Close

10 The Nonconformist

11 Return of the Native

12 Good-bye to Fiction

13 Good-bye to Chicago

14 Knitted Backward

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Credits

Index

1

CHILDHOOD DAYS

Take me out for a joy ride

A girl ride, a boy ride,

I’m as reckless as I can be,

I don’t care what becomes of me.

—REN SHIELDS AND KERRY MILLS, “TAKE ME OUT FOR A JOY RIDE”

Who’s yer fayvrut player?

—NELSON ALGREN, CHICAGO: CITY ON THE MAKE

Nelson Algren’s first memory was of getting lost, looking for a hero. He was two and a half. Taking another small boy, he walked up the sidewalks of Detroit in 1911, away from the house where he was born at 867 Mack Avenue, away from his mother’s candy store, into the vastness of the booming city, a golden-haired boy in short pants. He was looking for his uncle Theodore, a sailor who had worked on the big boats on the Great Lakes. Nelson’s mother, Goldie, who never entertained notions, only convictions, loved to talk about Theodore and her other astonishing brothers. She told how Theodore had gotten into a fistfight with the ship’s cook on the deck of the steamer Chicora. The captain said one of them had to leave. Theodore was proud—he knew he’d work again on one of the thousands of steamers and barges filling the country’s upper Midwest, on Superior and Erie and Michigan, the lake Nelson later referred to as the “secondhand sea.” So Uncle Theodore shook hands with everybody except the captain, and got off at Benton Harbor, Michigan. On its next trip, in January of 1895, the Chicora left from Milwaukee and sank without a trace beneath Lake Michigan’s wintry waters. Even a secondhand sea can be a devourer of men.

But this was not the best part of the story, Goldie would insist, speaking from atop a step stool, where she was sponging a wall, or from her knees, scrubbing a floor, her thick, blonde hair frizzing in the heat. The son of a fireman on the Chicora went looking for the wreck in a glass-bottomed boat called the Chicago. But in less than a week the glass-bottomed boat and the fireman’s son went down too. The glass-bottomed boat story was a bit much, and Algren’s father, Gerson, an overburdened working man always waiting to go another shift, had his doubts. He thought the son was a damned fool to follow his father.

“Not all the damned fools are at the bottom of the lake,” Goldie would snap back. Algren’s memories of his parents’ relationship were mostly of quarrels, the two of them circling round and round the ring, with Goldie forcing Gerson into rhetorical corners, where he would hide, rope-a-dope, behind the evening paper, his lips moving as he read.

But Uncle Theodore was no fool. Nelson urged his companion down one sidewalk after another, past the wooden balloon frame houses of laborers like his father, working for “the screw works,” or for Packard or Ford. What were the screw works compared to the open water? Goldie had taught contempt of ordinary labor early.

A train came by and the tiny boys waved to the engineer. “That was Uncle Theodore,” Nelson told his friend, trying out an early gift for improvisation. He was satisfied, but still lost. Everything was so enormous. A Jewish tailor found them and gave them rye bread before calling the police, his many children looking on. Perched on a policeman’s desk, eating ice cream, Nelson remembered the guns behind the desk, black and mysterious.

Nelson Algren was born on March 28, 1909, in Detroit, as Nelson Ahlgren Abraham to Gerson Abraham and Goldie Kalisher, two Chicago transplants and nonobservant Jews. He was a late baby and only son—his sister Irene was nine, and his sister Bernice was seven. Gerson was already forty-one, and Goldie thirty-one. Both his parents had come from big families. Besides the heroic Theodore, there was Goldie’s big brother, Abraham, and little brother, Harry, a sailor on the USS Chicago who had served in the Spanish-American War. He died at age twenty-nine, the year before Nelson was born, becoming the family saint. There were Goldie’s sisters Hannah and Toby, who on a summer evening used to sing, accompanied by the player piano, in memory of Harry:

My brave boy sleeps in his faded coat of blue

In the lonely grave unknown lies the heart that beats so true

His grandfather, who treated Nelson as a special favorite, showed him how he could blow real smoke through a little wooden clown.

The Kalishers were a “prosy family,” Nelson remembered. Goldie’s parents, Louis and Gette, were middle-class German Jews who came from Prussia to Chicago in the nineteenth century, and became embarrassed at the Polish Jews who followed them and looked so Jewish, with their yarmulkes, beards, and prayer shawls. Families like the Kalishers “knocked themselves out to repudiate their Jewish roots immediately,” Nelson said. As in Germany, “They were

anxious to become blonde and blue-eyed, which they succeeded in doing.” Towheaded Nelson must have pleased them.

German, not lower-class Yiddish, was spoken at Grandpa Kalisher’s home at 862 North Washtenaw in the West Town neighborhood, where he made red-banded “Father & Son” cigars and kept a sommerhaus, a European-style cottage, in the back. Goldie taught her son the German version of “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep,” which starts: “Ich bin klein / Mein Herz ist kein,” translated as “I am small / my heart is pure.” Nelson would tell his friend Art Shay that Goldie gave him some of his German toughness.

This was one kind of immigrant—hardworking, home owning, joining the American Legion and assimilating. On Gerson’s side was the opposite kind: the renegade, the lunatic, the crook. This was the type that fascinated Nelson, and this type keeps reappearing in his fiction, the one with the hustler’s blood, and in his own life of petty thefts, swindles, and sometimes ruinous gambles. This was Nels Ahlgren, his Swedish grandfather, born in Stockholm, Sweden, to a shopkeeper in about 1820. When Nels was a teenager, his father—Nelson’s great-grandfather—died, and Nels read his much-marked copy of the Old Testament. “When he did, it drove him bonkers,” Nelson recalled. Nels memorized the book, became an Orthodox Jew, changed his name to Isaac Ben Abraham, and moved to America before the Civil War.

Isaac went first to Minnesota as a fur trader, where he was burned out in an Indian raid. Then he went to Chicago and brought misfortune to a little servant girl from Koblenz, Germany, named Yetta “Jettie” Stire, sixteen years his junior, by marrying her and moving her to the swampy wilds near Black Oak, Indiana, which later became part of Gary, squatting on land he did not own, as Nelson recalled the story. Before trying his hand at farming, Isaac opened a country store and conceived an ingenious con, giving his customers Swedish pennies instead of American ones in change. The Swedish coins were worth about a third less. When he ran out of them, he tried making his own. Though Nelson does not elaborate on Nels’s methods, he believed his grandfather also experimented with perpetual motion, the eternal chimera of shiftless intellectuals.

A squatter farm and a crooked store among the mosquitoes and coyotes of Black Oak were not scope enough for a man of Abraham’s peculiar genius, so he took his wife to San Francisco, leaving at least one child behind to collect later. On the West Coast, while waiting for a boat to the Holy Land, Abraham became a sort of freelance rabbi, scolding his fellow Jews for their lack of orthodoxy, able to quote the Bible word for word. He made such a nuisance of himself in San Francisco that the chief rabbi would hide from him. When Swedish Isaac came knocking, someone would be sent down to say the rabbi was not home. Abraham would leave abrasive notes, mocking the rabbi’s intelligence. “He was an intellectual before his time, which was his trouble, inasmuch as he didn’t want to work,” recalled Nelson, who looked like him. Nelson’s father, Gerson, named for the son of Moses, was born in San Francisco in 1867. His sister Hanna was born later.

Through some mysterious appeal, Isaac gained enough money for passage to Jerusalem for himself and his family. Nelson doesn’t explain in his memoirs, but Abraham may have hooked into one of the early Zionist movements to create Jewish settlements in Palestine in the late nineteenth century, settlements that included Mishkenot Sha’ananim in Jerusalem. Gerson would later tell his own son he remembered camels as a small boy. How terrible this strange land must have appeared to poor Jettie, this desert country full of hard men, speaking a language that was neither German nor Yiddish nor English. As Nelson told it later, she was stuck doing all the work for Isaac and his hangers-on, sewing and cooking while missing Indiana. She soon had enough of the Promised Land. She went to the American Consulate, begging for release, and miraculously was given passage money, in one version of the story. Gerson walked down a dusty road with his mother, leaving Jerusalem as a young boy in 1871. What visions Jettie must have told him as he trotted in the strong Palestinian sun, of lush trees and fat cows, of actual rather than prophetic milk and honey. Gerson must have loved his mother, for as an adult he worked always with hands, and despised men who wouldn’t work and follow the rules. But as mother and children walked away, the Swedish prophet called after his meal ticket, “Hey! I’m coming with you.” So what could she do but take him back?

On the steamer back to the States, the blue-eyed prophet struck again. He looked at the American Consulate’s money and decided that here was a sin—thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, sayeth the Lord, but lo, were not these graven images of George Washington on the bills? So Isaac threw the money into the Atlantic. He did this publicly, for the edification of the horrified passengers, as Nelson told the story. Someone took up a collection for Jettie, and she kept the money hidden, to spare everyone another commentary on the first commandment.

In Indiana Isaac stayed on the farm with his family at least until 1880, when Gerson was thirteen, fathering two more children—Rosa and Adolph. Then Isaac abandoned his family and Judaism, first for socialism, then for Methodism, then for whatever would pay, going around the world as a mercenary missionary, as Nelson recalled. His sister Irene described the old man in softer terms, as a “writer and a lecturer and a champion of the underdog,” like her brother. The Abraham family went to Chicago, to the colonies of Jews on the West and North Sides. But when Gerson was about twenty, the old man returned, small and poor, with a long white beard and a new humility, ashamed that he had abandoned his family. “There is no truth, there is no religion, no truth,” he told them. “It is all nothing.”

His family pressed him to stay, and he did for a little while, at least long enough to be on the 1890 voter registration records in Chicago. Then Gerson remembered giving Isaac a half dollar and watching the little, hunched old man go down the aisle on the Madison streetcar, never to be seen again. He eventually died a pauper in Florida. In 1900 Jettie was living in Chicago with her oldest son, Moses, and daughter Rosa, at the same address as the newly married Gerson and Goldie. By 1921 Jettie was living alone as a widow, in the rear of a building in Hammond, Indiana. There was a long connection between Nelson’s family and northwestern Indiana, from the 1860s, with the farm, into the 1930s, when his sister Bernice and her friends bought a cottage there, through the 1950s, when Algren bought his own home in Gary, in the Miller Beach area. Northwestern Indiana was Algren’s alternate home, outside of Chicago, his version of the country and a green place of escape. He always longed to be able to look out on a big body of water.

It is a sign of Algren’s eccentricity that he later sees Isaac Abraham as his true spiritual father. But the homage started at Algren’s birth. Despite memories of the lonely road with camels, Gerson named his only son for the prophet wanderer: Nelson Ahlgren Abraham. Maybe this was a measure of Gerson’s own search for a hero, and hopes for something that only occasionally materialized.

Gerson got little schooling and was a working man from early adolescence, from a time when men worked from first light to 6:00 pm. He had seen the belly dancer Little Egypt at the 1893 World’s Fair, and a band called McGuire’s Ice-Cream Kings at the Columbia Dance Hall on North Clark Street, but these were short breaks in a life of constant effort. The great machinery of industrial-age Chicago wanted workers who weren’t throwing bombs and would endure a sixty-hour, six-day week. Gerson worked for McCormick Reaper Works, Otis Elevator, and Yellow Cab, fixing what was broken. He is described as a “screw maker” in the 1890 census. He was, Nelson remembered, “a fixer of machinery in basements and garages,” working hard and trying to avoid trouble at a time when trouble was everywhere, in greedy owners or threatening union agitators. Nelson suggested that his father was a scab, a strikebreaker, who would earn two times what others were getting for doing the same work until “some picket would take him aside and ask him how he would like to have his head blown off his shoulders.” Simple Black Oak Gerson replied he would like to wait until after lunch. Gerson saw the police clash with union activists advocating for an eight-hour day near the McCo

rmick works in May of 1886, perhaps ducking his head as he crossed the picket lines. Two workers were killed when police fired into the crowd. This incident was followed the next day by the notorious riot at Haymarket Square, in which a homemade bomb led to the deaths of seven policemen and four civilians, and later to the hangings of four anarchists on dubious evidence. Gerson also recalled seeing the fierce, bearded preacher-anarchist Samuel Fielden, who was later convicted of inciting the crowd to violence, speaking at the lakefront, which suggests that Gerson was willing to see all sides of the matter. But Nelson said with a note of scorn that Gerson did not remember these epic events as well as he remembered popular songs from the past—Gerson was not trying to be anybody’s hero; he was just trying to fix things.

In 1899, at age thirty-two, Gerson married twenty-two-year-old Goldie Kalisher and lived for a time with Jettie on Chicago’s North Side. Then they moved with baby Irene to Detroit, a growing city where the auto industry was just starting to take off and jobs were thick on the ground. Goldie worked as a candy maker. Nelson’s adored older sister Bernice was born there in 1902, followed by Nelson seven years later. His sisters helped care for him, pushing him around the neighborhood in a baby carriage to give Goldie a break. They moved back to Chicago in 1913. Gerson and Goldie must have saved some money from Packard, since they came back not to the bustling Near Northwest Side, under the eye of Goldie’s family, but to the pleasant, almost rural Park Manor neighborhood, to buy a two-story house at 7139 South Park, now Martin Luther King Drive, when Nelson had just turned four.

Then as now, Chicago’s neighborhoods were defined by Catholic parishes, and Park Manor was under St. Columbanus, the patron saint of motorcyclists, the cross of its combination church-and-school building standing sentinel over all the little one- and two-story brick and frame homes. Park Manor had yards and open prairies for playing Run, Sheepy, Run, cowboys and Indians, or baseball, with boys discussing the heroic White Sox—Shoeless Joe, Eddie Cicotte, and Nelson’s favorite, Swede Risberg. In the war years, it was the Huns versus the brave Americans and English, with boys taking turns as enemies and allies. They used sunflower stalks as bayonets, and garbage slop tied up in scraps of burlap as grenades. They talked over tin-can field telephones, connected by wires through wooden fences, and feigned dramatic deaths in trampled prairie grasses. Trenches could have been reinforced with stolen red bricks from the St. Columbanus construction projects—ambitious pastor Dennis O’Brien finished a convent in 1917 and later started building a big, double-steepled church, which was completed in 1923. Nelson grew up with this example of constant progress outside his window, of the city around him constantly expanding, with scaffolding and walls rising and the clanking noises of machinery.

Algren

Algren